So here we are, 2,000’ AGL, 120 KIAS in moderate turbulence over the Rockies. The terrain is seven to eight thousand feet above sea level. We have another twenty miles until the Front Range and the terrain drops off into Denver. We can’t move the ailerons! The aircraft is stable and heading east. At least we are flying. In a few minutes we will get a 4,000’ altitude relief as the terrain drops away. Just keep it steady until then.

As a cadet at the United States Air Force Academy I could not have outside employment.

I had worked very hard for my CFII and I really wanted to instruct. The only way was to hang a shingle in Denver and make the two hour drive up each weekend to avoid

being caught. I teamed up with an FBO that had about ten different airplanes for rent…and cheap! This was 1998. I could buy ten hours block in a C-152 Aerobat for $24/hour. I could get and RG (retractable gear) airplane for $55/hour.

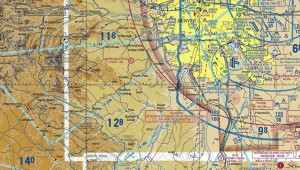

Our mission today was a mountain checkout for my student Greg. We had tried multiple times to get up into the mountains, but in a light airplane in Colorado, you just don’t fly when the winds aloft at 12,000’ are 25 knots or more. Like water running over river rocks, this creates massive turbulence. Today the forecast is right at 25 knots. It might work, but will be bumpy. There will be large updrafts and downdrafts in and around the passes. I chose the C-177 Cessna Cardinal because it was a retractable gear airplane and Greg wanted experience in retracts as well. Also, while slightly under-powered, it is an ideal demonstrator in the mountains. In the mountains you need to seek the rising air and avoid the sinking air. This becomes even more important in an under-powered airplane.

I walked in the office and asked for the logbook for the airplane. The secretary gave it to me but said they “had been working on the aileron bolt, but it is fixed now.” I had no idea what an aileron bolt is. Still don’t today. I went to the airplane and gave it a VERY thorough preflight. Like every other airplane on the line, multiple radios and navigation aids were placarded inoperative. Likewise, the autopilot was inoperative and had the same crusty plastic collars keeping the breakers pulled. The shoddy maintenance was how they kept their prices so low. Overall though, the airplane fired up and checked out OK. For a 22 year old CFII, it would do the trick.

We departed early afternoon for a tour of the highest passes in Colorado with planned stops at Leadville (The highest airport in N. America) and Aspen. As soon as we neared the Front Range, the bumps began, but they were manageable. At 10,000’ we went from almost 5,000’ above the ground to about 2-3,000’ above the ground as we crossed into the mountains. We neared our first small pass. The bumps got worse. The updrafts and downdrafts weren’t a problem, but the chop was. Just into our first pass I decided this wasn’t going to be the day. The turbulence was too much. We did a route reversal and headed back towards Denver. You just can’t push mountain flying.

Towards sunset you can see the passes sparkle. It looks like tin foil. Those are all the airplanes that pushed it lying there a few hundred feet from the top. There are hundreds up there. I actually advised two flatlanders not to fly in the mountains on a windy day. It was their first time crossing The Rockies. They were from Ohio. The last words that man uttered on Terra Firma were to me: “Yeah, whatever kid.” They impacted the terrain about an hour later, 100 feet from the top of the pass. It took a week to get their bodies out.

After we turned around, Greg and I settled in for the cruise back to Denver. About ten miles from where the mountains drop off to Denver, it felt like we hit a brick wall! BAM! Just one bump. I looked over at Greg and he looked shaken. I asked “are you OK?” He said “I CAN’T MOVE THE AILERONS!!!” I didn’t skip a beat, he must be mistaken. “I have the controls” I said. As I went to shake the ailerons to signify change of aircraft control, they were frozen. I shouted “WHAT DID YOU DO!?!?!”

Wind the clock. That’s what you need to do in any emergency. Move slowly and deliberately. Making even a single mistake this far into the accident chain could be your last. We are maintaining altitude and airspeed. We are headed to lower terrain. If we do nothing for the next 4-5 minutes, we get 4-5,000’ of altitude for free. I thought if nothing else, we can descend into the plains of Kansas and make a controlled descent into a nice farmers field. At around 110 kts, I like the odds for that. The last thing we want to do now is cause the airplane to go out of control.

you need to do in any emergency. Move slowly and deliberately. Making even a single mistake this far into the accident chain could be your last. We are maintaining altitude and airspeed. We are headed to lower terrain. If we do nothing for the next 4-5 minutes, we get 4-5,000’ of altitude for free. I thought if nothing else, we can descend into the plains of Kansas and make a controlled descent into a nice farmers field. At around 110 kts, I like the odds for that. The last thing we want to do now is cause the airplane to go out of control.

US: “Denver Approach, Cardinal N1234 Emergency”

APP: “Cardinal N1234 Emergency, Denver, go ahead.”

US: “Cardinal N1234 is 35 WSW at 10,000’ with a flight control problem, requesting possible divert into Centennial.”

The standard radio exchanges about fuel onboard, souls, etc. ensues. I come up with the game plan that if we can control the airplane I want to land to the north at Centennial as I am closely aligned for an approach to the north. Centennial is busy and had two runways departing to the south. As I got within 20 miles, they shut down departures for us. Now, how to land? The USAF teaches a controllability check. See how slow you can fly configured in your landing configuration, and once you find that speed, add a few knots, don’t go below it and land. Once we are past the Front Range I start slowing the airplane, trimming and slowing very slowly. At around 90 kts, the airplane starts rolling a little right. I had been using the rudders for these shallow banks. Now it is getting worse, 20, 30 degrees…I start to push hard against the control column. The airplane rolls harder right. Everything I do left makes it go right more. Now we have lost it, 90+ degrees bank to the right, 20+ degrees nose low, and the airspeed is increasing. Then, a voice from my instructor from my instrument training at 17 years old:

Now, how to land? The USAF teaches a controllability check. See how slow you can fly configured in your landing configuration, and once you find that speed, add a few knots, don’t go below it and land. Once we are past the Front Range I start slowing the airplane, trimming and slowing very slowly. At around 90 kts, the airplane starts rolling a little right. I had been using the rudders for these shallow banks. Now it is getting worse, 20, 30 degrees…I start to push hard against the control column. The airplane rolls harder right. Everything I do left makes it go right more. Now we have lost it, 90+ degrees bank to the right, 20+ degrees nose low, and the airspeed is increasing. Then, a voice from my instructor from my instrument training at 17 years old:

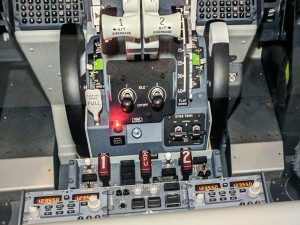

“If an airplane ever fights you, disable the autopilot and trim.”

That’s it. Just that one phrase, only today with the aileron bolt broken and a windscreen full of dirt, it didn’t seem to apply. That being said, my instructor, LTC Oscar C. Mack, USA (ret.), was always right. It was his way or the highway.

I already had the electric trim switch on the control column off. The autopilot should still be inop. Still though, I looked across the cockpit in front of my student and found the control head for the autopilot. The master switch was on. I flipped it off. Instantly the controls snapped back to life. We were in 120 degrees right bank and about 25 degrees nose low. I did a nose low unusual attitude recovery like I had done a hundred times before in aerobatic training. Upon returning to straight and level, we both breathed a sigh of relief.

During that massive jolt in turbulence, Greg’s knee had hit the autopilot master switch on. Neither of us thought about an autopilot issue since it should have been disable and also were focused on that mysterious ‘aileron bolt’. Somehow the autopilot had managed not only to be powered and turned on, the clutches that allow you to overpower it were set incredibly tight. Someone had erroneously over torqued the slip clutch nut at some point in the distant past. We never applied maximum brute force in fear of breaking a flight control.

We did a straight in to Centennial and landed to debrief the situation.

Flying Boeing wide bodies now, every time we are in the sim with runaway trim, I think of Oscar. Thank you Oscar.

LTC Oscar C Mack died after his tour in Vietnam on 01/07/1998 at the age of 57. He commanded over 900 Dustoff medical rescue missions. He never lost a crewmember.

Ridgeland, SC

Flight Class 62-10

Date of Birth 12/16/1940

U.S. Army